A logic teacher I once had told us that an intuition is like a container, it comes packed with the information you will need in order to realize what you sensed in that intuitive moment, but it must be unpacked.

That statement describes how I go about writing.

I begin with an intuition or what I call “an intuitive hit.” Another way to say this is that I begin with an idea that is emotionally meaningful to me and is pregnant and filled with possibilities. But the details of the story unfold only as I unpack the hit.

How do I know that this will work?

Because of my emotional response, the resonance I feel, the conviction that I am on to something. I have been touched deeply and it’s worth pursuing.

I don’t know what those possibilities are when I begin. In fact there’s no way I can know. Because an intuition is an invitation into mystery, the mystery of the story.

I don’t mean a mystery story, intuitions can result in love stories, sports stories, political stories. I don’t believe you can have an intuition sufficient to motivate you to write outside of what you are usually are interested in.

So when an intuitive hit occurs, I have to pay attention. It’s the entranceway into a gold mine of feelings, images, ideas that become the marrow of the project, a book, a short story, a screenplay.

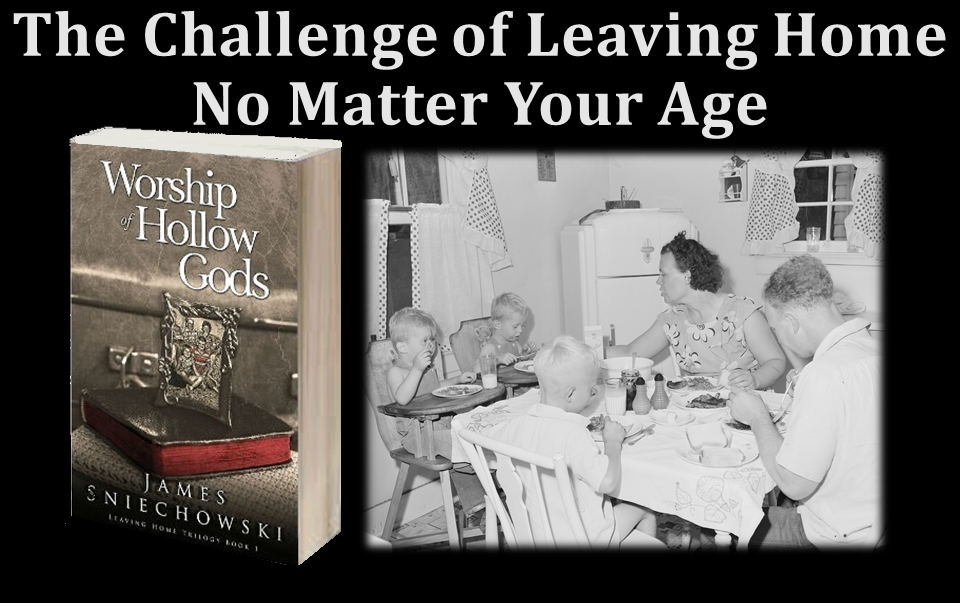

For example, one of my favorite themes is Leaving Home. I don’t mean the obvious understanding of leaving home—moving to a different house in a different city, or state, or country for that matter. That’s a superficial meaning of the phrase Leaving Home.

The home I am referring to is the psychological home we all carry with us, in the unconscious mostly, as a result of the experiences in our early family life. To leave home deeply, fully, and effectively, requires effort and self-awareness, which are qualities that do not come with birth but must be developed.

In the first book of my Leaving Home trilogy I began with a one-line hit: “Shot and a beer,” Uncle Bo shouted as he walked through the back door, his wife, Irene, in tow. This moment is the first line of my first book, Worship of Hollow Gods. The page opens on a kitchen scene in the home of my parents in Detroit in 1950. Relatives are gathering for a poker and pinochle party— a family ritual. From that intuitive hit a 203-page novel emerged.

I say emerged.

I have learned to trust such intuitive hits and know that they contain all that I need to complete whatever the project is.

Because of my trust, I don’t then lay out a plot. Why not? Because I don’t know the plot. The plot will emerge as the story is being told. Or to say it another way, as the story tells itself as the characters interact and I follow along.

What I do next, after the hit; I begin writing because, in truth, there is nothing else to do. I build my stories around the interaction of the characters organically evolving in situations. And as long as I am honest with the storytelling, the characters who exist inside the intuition will come forth. It’s my job to listen and follow.

I do not impose on a story. That’s to say, I don’t manipulate them to make sure a plot works. I let them lead and the plot comes to life. In that way my writing is very intimate, of the moment, producing a fluidity that makes the reading easy, carrying the reader along. My process makes writing joyful for me—a process of discovery for me and the reader.

The moments in the story are authentic to the story because they belong to the story and not to me. They emerge out of situations and are not known beforehand. This approach protects against predictability. I’m sure you’ve read books or seen movies that from the first moments you know how they will end. You can almost predict the development. That takes the pleasure out of reading, out of being the author’s imaginative partner.

Intuitive “hits” don’t just happen at the beginning of writing, and, of course, when I feel them they must be followed throughout the storytelling. They can change the course of the story and can take it in directions you have to explore to be able to express. Trust your intuitive hits, they are loaded.